The Novel

Jane Austen’s acclaimed novel Pride and Prejudice initially published in 1813 is an complex and in-depth examination of the rural upper-class society in 18th century England. While I use the world upper-class a clear distinction must be made as Austen distinctly writes about the landed gentry, that is to say Gentlemen with inheritable estates, and not about the Aristocracy—those who wold titles, in other words the Nobility. The events of Pride and Prejudice, therefore, primarily take place within the confines of an intimate rural community and reflect the unique concerns of its individuals. As a result, the residents of Longbourn and it’s surrounding community all function according to their own rules of propriety —rules which outsiders like Mr. Darcy and the Bingley’s have to accommodate to (or not in Mr. Darcy’s case). In Pride and Prejudice Austen closely dissects the social landscape of these intimate communities, but she also parallels the reader’s experience through the evolving relationship between Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet. Indeed, the world of Pride and Prejudice is one that is heavily reliant on the written word, and many times it is only through this medium that the difference between fiction and reality can be discerned by both the reader and character, but I shall speak more of that later.

In modern day, Pride and Prejudice is often misinterpreted as a romantic love story between Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet. This sentiment is no doubt fed by the popularity of the romantic in modern culture but also by virtue of the main concern in Austen’s novel—marriage. Marriage in Austen’s world, however, does not function the same as does marriage in society today. Far from being an expression of love, for the characters of Pride and Prejudice marriage is primarily a financial bargaining chip and a tool for upwards social mobility. In fact, Austen goes through considerable lengths to demonstrate the perils of an unwise marriage based on fleeting passions rather than sense. This is, of course, exemplified in the disastrous marriage between Mr. Bennet and Mrs. Bennet, and again, in the marriage between Lydia and Mr. Wickham.

Her father captivated by youth and beauty, and that appearance of good humour, which youth and beauty generally give, had married a woman whose weak understanding and illiberal mind, had very early in their marriage put an end to any real affection for her (p. 180).

As Austen demonstrates, an unwise marriage can either make or break an individual and for a family like the Bennet’s whose estate is inherited solely through the male line, a good marriage is absolutely necessary. Mrs. Bennet’s obsession with marriage while undoubtedly comical is tempered by the underlying, and very real, possibility of destitution in the case of Mr. Bennet’s death. A child of an dysfunctional marriage bereft of respect, Elizabeth cannot bring herself to accept someone she does not respect and indeed when she eventually decides to accept Mr. Darcy’s addresses it is this sentiment that she expresses rather than romantic love.

She respected, she esteemed, she was grateful to him, she felt a real interest in his welfare; and she only wanted to know how far she wished that welfare to depend upon herself (p. 201).

Thus, Elizabeth’s marriage to Darcy is much more about finances and respect than it is about romantic affection. Wealth also plays an incredibly important role in this society specially in relation to an individual’s marriageability for it can work against you (like the Bennet’s) or in your favor (like the Bingleys’). Indeed, it is Bingley’s wealth which essentially makes him an eligible match for the impoverished but genteel Bennet’s (and it is equally interesting that the woman he chooses to give his affections to is the daughter of a landed gentleman and of the highest local rank). The Bingleys’ wealth, after all, is in fact derived from trade, a fact that Miss Bingley and Mrs. Hurst choose to forget (instead focusing on their good connections) even as their social difference is felt by those of higher social standing such as Mr. Darcy who is often as condescending to Miss Bingley as he is to the local residents. Austen, however, never lets us forget how much each person is worth and the consequences of rank is felt in Miss Bingley’s desperation for the purchase of an estate. The community of Longbourn, is therefore, one that is intimately concerned with individual monetary worth and social status and while Mr. Darcy at first evidences disdain at what he deems vulgar behavior, it is only through his interaction with Elizabeth Bennet that he is able to recognize his own lack of propriety.

The Film

Gurinder Chadha’s (2004) innovative film adaptation “Bride and Prejudice” is a colorful romp that mixes stylistic techniques of Bollywood, Hollywood, and British film traditions and places Jane Austen’s classic tale in a modern setting. Despite the fact that the film has received many negative reviews there is still much to be lauded in Chadha’s “Bride and Prejudice.” Perhaps one of the strongest points of Gurinder Chadha’s film is in its presentation of womanhood, embodied in Lalita and her sisters, which work to dispel the traditional submissive/passive image that is found in both Eastern and Western film.

In her article “Brides Against Prejudices: New Representations of Race and Gender Relationships in Gurinder Chadha’s Transnational Film ‘Bride and Prejudice’ (2004)” author Elena Oliete points out the prominence of the female roles in Chadha’s film even over the characteristically popular male lead.

“In opposition to Bollywood movies, in Bride and Prejudice female characters that have a preponderant role. Whereas Martin Henderson’s performance of the hero, Mr Darcy, loses the tremendous appeal Colin Firth granted to him in the popular 1995 BBC version of the novel, the heroine, Lalita (Aishwarya Rai) recovers the original force of Austen’s Lizzy had in the novel.”

Oliete’s point is incredibly accurate as Lalita, perhaps more so than her sisters, continuously defies both the traditional Bollywood stereotype of women as the submissive wife/mother and Western stereotypes about Indian women. Chadha constructs Lalita as an independent, outspoken woman with her own ideals and furthermore sets her up as the apparent heir to her father’s business as depicted by the scenes that show her riding around the farms and crunching numbers at the table. In no other point in the movie is the female sensibility more apparent than in the musical number “No Life Without Wife” for it is here amidst the stereotypical portrayal of marriage (working man and stay at home wife) that Lalita voices her own expectations and desires regarding relationships and marriage.

As a director, Chadha is also successful at challenging Western stereotypes regarding the East. Indeed, Darcy’s reasoning and attitude often voices common western attitudes towards foreign countries in both the economic and social realms, and it is during these times that Lalita acts as the foil to Darcy’s western prejudices opening up the door to a different perspective. As Cheryl Wilson states in her article “Bride and Prejudice: A Bollywood Comedy of Manners”:

“Bride & Prejudice is a multinational, multi-cultural crowd-pleaser that touches on American imperialism, the way the west looks at India and what people regard as backward or progressive. In a populist, entertaining movie the drama is questioning the audience’s Eurocentric attitude”

Most of the interactions between Lalita and Darcy happen in this sphere of cultural exchange that essentially end with both parties realizing (and discarding) their own prejudices of culture. Lalita’s impression of Darcy is negatively affected from the start first by his curt refusal to dance with her but secondly, and perhaps more importantly, by his callous dismissal of the local accommodations despite having the best room. As the conversation progresses Darcy eventually states “That there is nothing wrong with having standards” to which Lalita replies ” No, as long as you don’t impose them on others.” From this point on Lalita’s impression of Darcy is decidedly negative and colored by her own prejudices at what she perceives as implicit American Imperialism. It is in this multi-cultural sphere that Chadha excels in portraying, and essentially diffusing (at least in film), cultural stereotypes.

The Adaptation

In previous sections I mentioned that Jane Austen’s novel parallels the experience of the reader reading the novel primarily through the developing relationship between Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet. Indeed, throughout the novel characters frequently refer back to previous conversations or events so that the very structure of the novel encourages revision. It is no coincidence then that Elizabeth Bennet’s understanding of Mr. Darcy’s character happens through the means of a letter which she continuously re-reads. It is in this section that Austen peels away the fiction to reveal the truth of Mr. Darcy’s nature for both Elizabeth and the reader forcing both to revise and re-imagine previous scenes. It is notable as well that Elizabeth’s first reading of Darcy’s letter is read with prejudice and it is only through her second perusal that the truth becomes available. This aspect of Austen’s work is one that is not only difficult to adapt, but one that is completely removed from Chadha’s modern adaptation. Despite this however, Chadha does use her own sort inter-textuality within the film but that effort is, nevertheless, often confusing and lacking as author Christine Geraghty points out:

Fears that this mix might confuse the audience can be seen in the publicity for the film which tried to stabilize its genre. The cinema trailer ended with the reassurance that the film was indeed that Hollywood staple, a romantic comedy, a generic labelling reinforced by the tag line which declared ‘Bollywood meets Hollywood…. And it’s a perfect match’, a description which ignored the film’s British qualities. The varied elements do not work in a uniform way. Different aspects of the story are underpinned or amended in different ways by this layering of references.

Another key aspect that makes modern-setting adaptations of Pride and Prejudice difficult is the importance of conversation and social interaction that is present in Pride and Prejudice. In Longbourn Austen’s characters are severely limited in their interactions with the opposite sex as they must follow the rules of propriety, in addition social interaction and events are a prominent part of daily life. Indeed, in Longbourn and its surrounding communities characters are often socially engaged with their neighbors whether it be through daily visits or through lavish balls and dinner parties. As a result, misconceptions and fictions (read:gossip) are specially easy to spread and very hard to eradicate. This is primarily because, as in the case between Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet, propriety and civility must always be maintained and one did not simply ask difficult questions. In addition to this, the interactions between male and female were limited already to certain events such as balls and formal visits which usually involved many people. Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet’s relationship, therefore, develops slowly in this fractured way. This sensibility is a difficult one to transpose into a modern setting as social norms have drastically changed. The traditional Indian heritage of Chadha’s film attempts to approximate this sensibility as there seems to be an underlying (though definitely not as strict) social code of propriety. Furthermore, in Chadha’s film she does incorporate a scene where Darcy, Balraj and his sister visit the Bakshi’s which is awkward for everyone involved (except perhaps Maya). This awkwardness however adds a touch of humor to the film as it evokes the common, and dreaded, modern situation of meeting your significant other’s parents. In what Chadha does excel in however, is in casually and naturally representing the sexual tension otherwise removed from the film (there’s not even a kiss!) that occur in Austen’s novel through the mediums of balls and soirees. In Chadha’s version this is expertly transposed in the various traditional Indian gatherings which function in the same way as Austen’s balls. It is during these dances that the characters are able to feel the romantic tension and interact with each other.

Lastly, as I’ve discussed at length above, Marriage is an integral part of life in Longbourn society. It is a tool that is employed by women and men alike for upward social mobility or financial gain. For the Bennets, as discussed, Marriage is absolutely essential to their survival, without it the Bennet girls and their mother run the chance of becoming homeless and destitute should Mr. Bennet die. As the world of the Bennet’s holds little opportunity for the self-sufficiency of women, Mrs. Bennet and her daughters’ are put in a precarious predicament. In contrast, modern society holds entirely different views of marriage and though in her film Chadha uses Indian cultural norms in order to add importance and cultural relevance to the idea of marriage, it nevertheless falls flat and does not contain the same social significance as an integral part of the storyline. Indeed, while marriage is ultimately a central aspect of the novel, it is not so in Chadha’s film despite Mrs. Bakshi’s constant preoccupation with it. While there is social pressure put on the girls to marry, it is presented as more of an old-fashioned preoccupation, evidenced by the Bakshi sisters’ unenthused reactions every time their mother brings the topic up. Other than the traditional social norms there is no sense of urgency that the girls must marry. Lahki’s escape with Wickham too is changed to fit modern sensibilities, for unlike the Bennet sisters who would be ruined by association if Lydia’s situation became known, Lahki’s situation does not carry the same social significance. Instead, Lahki’s situation provides a glimpse into a more modern concern —that of internet predators luring the young into dangerous sexual encounters. This is reinforced within the film by Lahki’s and Wickham’s email correspondence which she hides from her family and by Wickham’s shady actions towards Lahki. In essence, Bride and Prejudice might not be a by-the-book rendition, and in fact, in order to fit the modern setting there were many aspects which had to be re-arranged, nevertheless Chadha does convey the overall spirit of Austen’s work while at the same time making her own socio-economic and cultural critiques on modern society.

Primary Source:

Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. Print.

Secondary Sources:

Oliete, Elena. “Brides Against Prejudices: New Representations Of Race And Gender Relationships In Gurinder Chadha’s Transnational Film ‘Bride And Prejudice’ (2004).” International Journal Of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences 5.5 (2010): 135-141. Web.

<http://web.b.ebscohost.com.proxy-um.researchport.umd.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=fd56a13a-4c4a-4b8a-90a1-fb78691d33a9%40sessionmgr198&vid=1&hid=124>

Wilson, Cheryl A. “Bride And Prejudice: A Bollywood Comedy Of Manners.” Literature Film Quarterly 34.4 (2006): 323-331. Web.

<http://web.b.ebscohost.com.proxy-um.researchport.umd.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=0fa96a3b-1717-42b3-803d-faf95d8d0a5a%40sessionmgr112&vid=1&hid=124>

Geraghty, Christine. “Jane Austen Meets Gurinder Chadha.” South Asian Popular Culture 4.2 (2006): 163-168. Web.

<http://web.b.ebscohost.com.proxy-um.researchport.umd.edu/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=30327001-9d2f-4645-8eda-ad3bc0623f7c%40sessionmgr113&vid=1&hid=124>

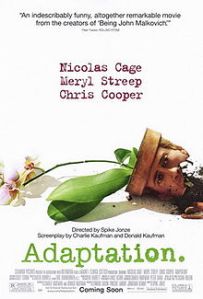

Orlean’s arc centers around her quest to find something that she is passionate about and it is this fervent desire that leads her to become more and more entrenched and obsessed with John Laroche’s story whom she believes embodies everything that is not: Namely, that he thrives off of passion (though some could call his behavior more obsessive rather than passionate). The effects of these passions and obsessions can be seen in the neurotic, anxious behavior of Charlie Kauffman and in the quiet desperation of Susan Orlean as she interviews and gets to know John Laroche.

Orlean’s arc centers around her quest to find something that she is passionate about and it is this fervent desire that leads her to become more and more entrenched and obsessed with John Laroche’s story whom she believes embodies everything that is not: Namely, that he thrives off of passion (though some could call his behavior more obsessive rather than passionate). The effects of these passions and obsessions can be seen in the neurotic, anxious behavior of Charlie Kauffman and in the quiet desperation of Susan Orlean as she interviews and gets to know John Laroche.